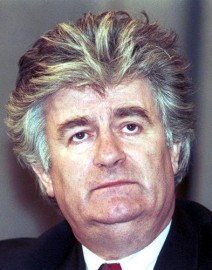

The apprehension of former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic has been widely acclaimed as a good thing. There are some, though, who disapprove.

There is a group of souverainistes who rate national sovereignty more highly than justice. The idea that someone should be tried in an international court repels them. Criminal justice is something that belongs only within states, they say, even though there are plenty of examples of states where the administration of criminal justice has broken down. Worse, some of the most appalling crimes actually involve the deliberate destruction of the criminal justice system, to ensure that a campaign of genocide can be implemented, for example.

(Daniel Hannan sets forward the argument here.)

The souverainistes are not suggesting that such actions as genocide are morally acceptable – don’t be in doubt about that – but they are insistent on defending a system that renders such actions beyond our capacity to prevent them. One might ask about the moral standing of an act that foreseeably permits others to commit immoral acts.

There is a separate criticism of international justice, which is that it is ad hoc and unreliable. (Daniel Hannan makes this point, too.) This is an argument not against the principle of international justice but against its practice. And they are right, in that ad hoc legal systems are less preferable to well-established ones. But in order to have well-established legal systems, one first has to establish them. Over time, they will develop experience and case law and tradition, which will make them more reliable and predictable in the future. Any institution has to start somewhere.

If the argument that the institutions of international justice are new is an argument against using them, they will never be set up. In which case, the worst dictators and criminals will remain beyond justice. And that cannot be preferable.