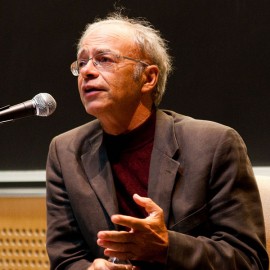

A new book by philosopher Peter Singer asks some awkward questions about the moral obligation to give to the poor. Peter Singer has for years examined the limits of what one person might be expected to do for another – he is here interested in ethics, not law – and his latest work, “The life you can save”, expresses this examination in clear and stark terms.

He opens with a simple example: what would we think of someone who declined to help a child drowning in a pond for fear of ruining an expensive new pair of shoes? It is hard to accept that a pair of shoes might be thought to be worth more than a child’s life. But go down the high street, and you will see people thinking this all the time, for to spend money on luxuries rather than donating money for the benefit of the world’s extreme poor is, according to Peter Singer’s argument, logically equivalent to standing and watching a child drown.

Something like 1.4 billion people around the world live in extreme poverty, with an income of less than $1.25 a day, and millions of them die each year as a result of being poor: their need for assistance is immense.

However, Peter Singer recognises that, taken to its ultimate conclusion, he is proposing an extraordinarily demanding standard, and any system that relies on extraordinary people rather than ordinary ones is not going to succeed. So, on the basis that he is aiming to maximise the number of lives saved rather than the number of rich people who live truly ethical lives, he outlines a more modest set of payments that the rich might realistically be asked to make to the poor (as though there were some kind of Laffer curve relationship between requests for money made and money actually received). (Read more about Peter Singer’s book here.)

This blog does not ordinarily deal with development issues as such, but there are two points of interest to federalism that arise from Peter Singer’s book.

The first is the notion of parochialism. People seem to be more willing to donate to causes or people near to them rather than to causes or people further away, even if the extent of need is greater further away. This is given as a reason why people do not donate towards reducing extreme poverty as much as they should (according to Peter Singer’s standards). It is not set out as something to be disapproved of; it is merely set out as a fact. Research by behavioural psychologists reveals a number of areas where human judgements diverge from the otherwise logical: illogicality in some respects is a biological part of human nature.

Federalists recognise this tendency towards parochialism, and have looked to the principle of subsidiarity as a means of accommodating it. This is the idea that different levels of government are needed to deal with different political issues, according to the size of the community that might be affected by them. The judgement on which communities are affected by an issue might be narrowly geographical – the people who live in the flightpath of an airport, for example – or it might be cultural – the people who speak French – but it might also be parochial.

Federalism is not the application of an abstract theoretical model but is the search for a viable political system for the real human world. (That is one of the reasons why it is taking time to develop, even here in Europe.) If parochialism is one of the features of the world in which we live, it is something that federalism needs to take into account.

The second point of interest is that, human nature notwithstanding, Peter Singer still searches for a solution to the moral problem that he has identified. He proposes a course of action that flows contrary to that apparent human nature but that nevertheless can be consciously chosen. It might not be instinctive to make substantial donations on the Peter Singer model, but it is possible.

Federalism is founded on the same notion, thinking about the inherent human tendency for violence. It proposes a conscious course of action to limit the consequences of that human tendency: the rule of law exists within states for this purpose and federalism would apply that rule of law to the actions of the states themselves as well as to the people within them. Parochialism needs to be acknowledged, for human reasons, but for moral reasons must not be surrendered to.