George W Bush won the 2000 presidential election arguing that America should turn away from the nation-building efforts that had characterised Bill Clinton’s foreign policy and focus more narrowly on specifically American interests around the world. His immediate focus was China, which he saw as a “strategic rival”, leading to crises such as the downed American navy surveillance plane that was forced to land in Hainan after a collision with a Chinese fighter jet in April 2001.

His attention was forced back to the Middle East by the 11 September attacks on the World Trade Centre and on Washington DC, at which point the neo-cons in his administration had a pretext for regime change in Iraq and America found itself back in nation-building on a scale even Bill Clinton would never have contemplated. Before the war in Iraq, of course, there was the war in Afghanistan and the removal from power of the Taliban. That war in Afghanistan is still with us (and with the Afghans), as are the nation-building efforts.

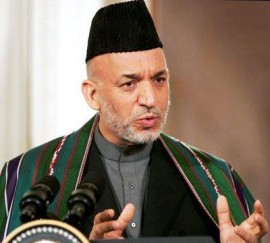

Hamid Karzai has been re-elected as Afghan president, which was a clear goal of western policy. Every country has a president, so Afghanistan must have one too; no matter that his government is rotten and corrupt, winning a fraudulent election that in many parts of the country did not really happen at all. This is nation-building.

It would have been better to have had a policy of democracy-building instead. Politics should start from the bottom with local elections, before rushing to elect a national president. Democracy needs to be based on the foundations of local participation, rather than suspended from international intervention from above. Nick Horne, a former UN official in Afghanistan, puts it like this:

“Afghanistan requires fundamental political reform — a stronger parliament so that power can be shared between Afghanistan’s myriad ethnicities, who can hold the executive to account; and decentralisation to enable Afghans to participate in governance within their communities — something much more in keeping with Afghan traditions.”

(Read his whole article here.)

The obsession with national politics is obscuring the more important concern about politics as such. Politics can, and must, exist at levels other than the national.

My second point about Afghanistan is the same one, but applied to the western armies themselves.

Given the current failure of strategy – 8 years of war and no closer to victory – politicians in Britain, America and elsewhere are thinking about what to do next. One idea is another surge, sending a lot more soldiers to the battlefield to try to win the war. Another idea is to redefine what victory means, abandoning the idea of creating a western-style liberal democracy where one has never existed before and settling instead for stability. If that means that the Taliban gets back into power and oppresses women again as it did before, then that is a price worth paying if it means an end to the flow of casualties back to Wootton Bassett and Dover Air Force Base.

Whatever decision is finally reached, about whether to escalate or withdraw, it is essential that the decision is taken and implemented collectively. A number of the problems that exist at the moment arise from a patchy and uneven implementation of the current policy. Some countries are willing to send soldiers to fight in Afghanistan, while others see their contingents as there to build schools and direct the traffic. One does not look at the western military presence in Afghanistan and see a coherent determination to prevail.

Barack Obama won his election to the presidency promising to re-engage with America’s allies around the world. Here is his test: can he assemble a collective international understanding and commitment to a new Afghan policy, or will he merely be able to lead America and one or two friends? Will he establish an American policy on Afghanistan, or a policy that might actually have the chance of success?