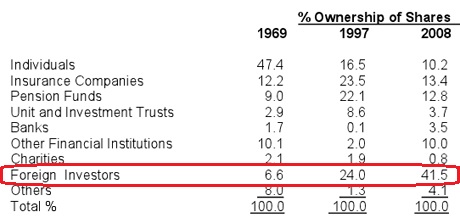

An interesting statistic reported by Professor Prem Sikka in the Guardian today, regarding the ownership of British companies. The proportion of the shares in UK-listed companies owned by foreign investors has increased from 6.6 per cent in 1969 to 41.5 per cent in 2008.

The traditional analysis of capitalism is that, like democracy, each country has its own variant. There are obvious features and principles in common, but German capitalism is different from French capitalism is different from Japanese capitalism and so on. An argument against international economic integration is that these different national versions of capitalism do not fit neatly together. Compare Greece and Germany, critics say.

But what is economic integration doing to the notion of a national form of capitalism?

The economic ecosystem of wages, profits, dividends and investments is no longer contained within national borders. Companies operate, and are owned, in more than one country.

That means that the ability of a national government to apply a stimulus to its own economy is weakened because much of the demand thus created will go abroad and not stay at home. An attempt to cling to a national conception of capitalism therefore has an inherent deflationary bias. Fine, if you share that deflationary instinct, not so fine if you don’t.

Even the people who oppose the euro – perhaps especially the people who oppose the euro – who nevertheless want a renewed economic stimulus applied to the economy (and I am thinking of the Labour party here) need to back a European approach to macroeconomics and not a series of national approaches. Can the Eds, Balls and Miliband, argue for such a combined approach, or will their resistance to the euro reveal itself as resistance to the EU as such?