By Brendan Donnelly

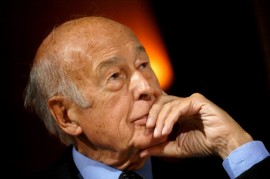

It is still unclear whether the Convention on the future of Europe, chaired since early 2002 by Valery Giscard d’Estaing and now approaching its final phase, will be a footnote or a major chapter in the history of European integration. Much will depend on what national ministers, meeting over the coming months in an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC), make of the Convention’s recommendations. IGC’s traditionally develop a negotiating dynamic of their own, only partly predictable by outsiders.

But if the reception to be accorded to the Convention’s work remains uncertain, we can already say a certain amount about the likely recommendations coming from the Convention itself. After sixteen months of sometimes frustrating work, the Convention’s conclusions will reflect on many issues a striking degree of consensus among most delegates; the recommendations will be largely federalist in character; and they will be considerably less congenial to the British government than Mr. Blair hoped as recently as last summer.

Few observers would have expected precisely this outcome when the Convention was first mooted in December 2001. For some it will be a pleasant surprise. For others, it will be a distinct disappointment.

For all the initial murmurings about his patrician style of chairmanship, Giscard’s leadership of the Convention has delivered considerable results. His main, and persuasive argument to delegates has been that the more of them supported an agreed text produced by the Convention, the greater that text’s chance of being taken seriously by the IGC. No doubt, even at the end of the Convention’s work, there will still be dissident voices from Eurosceptics and those favouring even more rapid and radical European integration. But Giscard seems likely to go to the European Council at Salonika in June with a text approved on many important points by the overwhelming majority of the Convention’s participants.

It is true that for Giscard sometimes “le consensus, c’est moi.” But to obtain consensus in the Convention, he has shown undoubted and sometimes unexpected flexibility. In particular, he has been willing to accommodate the federalist side of the argument much more than some hoped, some feared and most expected.

Giscard’s willingness to move in a federalist direction has been reinforced by a number of factors. There is within the Convention a substantial federalist block, wishing essentially to reinforce and develop the competences of the central European institutions. Giscard knows that consensus will not be achievable without them. Moreover, the existing structures of the European Union already contain substantial federalist elements, not always acknowledged or designated as such. Any work of constitutional codification, such as that on which the Convention is engaged, will inevitably highlight and, by highlighting, consolidate these already present federalist tendencies.

Giscard clearly draws in his own mind a strong dividing line between foreign, security and defence policy on the one hand, and the remaining, largely legislative activities of the European Union on the other. Like many French politicians, he sees foreign, security and defence policy as a matter best settled between national governments. As long as Europe’s institutions play only a small role in these areas, he is content for their legislative functions to be maintained, and even enhanced.

On this latter point Giscard has given a great deal of succour to the federalist case. In the first draft constitution of the European Union which he put to the Convention, Giscard recommended the generalization of majority voting in the Council and the wider application of co-decision between Council and European Parliament. Both these are long-standing federalist demands. But Giscard went further, describing in his draft constitution the Union as exercising its shared powers on a “federal” basis. The British government’s representative to the Convention, Peter Hain, has been unable ever since to conceal his irritation at this “unhelpful” formulation.

In general, the upshot of the Convention seems likely to be a disappointment for the British government, which at first overestimated the extent to which Giscard shared its intergovernmentalist agenda and its suspicion of the central European institutions. It may be (although this is controversial with the small countries ) that the Convention will recommend the institution of a long-term President of the Council, to act as Europe’s “voice in the world.” This will be seen as a success for the British, reflecting the Anglo-French conviction that foreign, defence and security policies should largely remain intergovernmental matters for the foreseeable future.

But nothing Giscard recommends will be plausibly presentable as a fundamental rebalancing of the European Union’s decision-making structure. Neither national Parliaments nor national governments will see their role in the workings of the Union significantly enhanced. On the contrary, the Union’s central institutions will be strengthened, not weakened, if the Convention’s likely proposals are implemented. Like its Conservative predecessor, this New Labour government has often accepted in its rhetoric the Eurosceptic parody of the European Union’s central institutions as dangerous breeding-grounds for the “European superstate” of popular legend. It will not be easy for Mr. Blair to explain why the Convention has come to so radically different a conclusion.

It seems probable that the Convention’s recommendations will follow hard on the heels of the almost certainly negative assessment by the British Treasury on the UK’s entry into the euro. Eighteen months ago, the present British government hoped that the outcome of Giscard’s Convention, which they would present as a “victory” for intergovernmentalist ideas, would help them win a euro referendum in 2003. Whether the Convention’s conclusions would in any event have played a significant role in a referendum campaign may be doubted. What is beyond doubt is that Giscard and his Convention have not so far played the role assigned them by British governmental strategy. Mr. Blair’s hope must now be that he can claw back the ground lost in the forthcoming IGC negotiations. Those who live longest will know most.

Brendan Donnelly is Chair of Federal Union and a former MEP. He is now Director of the Federal Trust, and may be contacted at [email protected]. This article was first published by FT Online. The opinions expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of Federal Union or the Federal Trust.