Straying from the discussion about the EU institutions for a moment, my eye is caught by the report on a debate about slavery in Bristol (read it in The Independent here).

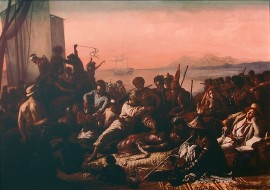

The question is whether the city of Bristol should apologise for the slave trade that was source of much of its wealth in the 17th and 18th centuries. Ships would ply a triangular trade, taking manufactured goods from England to West Africa, slaves from Africa to North America and the Caribbean, and then sugar and tobacco back to England. The Bristol merchants made a lot of money out of this, as did slave traders on the Guinea coast and plantation owners in the West Indies. The price was an immense amount of human suffering.

Slavery has been an endemic feature of economic life for millennia, but the sugar plantations in West Indies were the first industrial-scale slave-based trading operations since Roman times. Henry Hobhouse, in “Seeds of change”, calculates that a slave died for each ton of sugar produced. The gentility of Jane Austen’s England lived off the profits of this gruesome business, the income that sustained Mansfield Park being generated in Antigua, for example. (Edward Said traces the connections in “Culture and imperialism”).

The former practice of slavery is not incidental but fundamental to the wealth that England acquired at that time. The suggestion of an apology has to be taken seriously. There are even demands for compensation.

One argument offered against the need for a British apology for the slave trade is that the British in the end abolished it. Not only was the British slave trade ended in 1808, the Royal Navy took on the role of capturing slave ships from any other country. But it was not just the British navy that interdicted slave shipping, and it is hardly a defence of wrong actions that one stopped doing them.

Going further, Hobhouse describes how economic and moral interests combined in 1807 for the passage of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. Existing slaves were not freed (not until 1834, when compensation was paid to owners for their losses) so they became more valuable, not less; the shipping occupied by the slave trade was needed elsewhere for the war against Napoleon; the production of sugar by slavery was less profitable than the other nascent aspects of the Industrial Revolution in which scarce capital could be invested; and the actions of the Royal Navy ensured that British sugar production in the West Indies could not be undercut by cheaper slave-produced sugar from elsewhere. Funny how morality emerges on the side of the profitable.

So, if there is little moral high ground left to the slavers, what else might one say about the call for an apology?

Professor A C Grayling, also writing in The Independent, argues that focussing on an apology implies that slavery is a historical episode, whereas there are actually more slaves today than at any time in history. Furthermore, it was all a long time ago. “Apology is an important thing when made by actual perpetrators of wrongs to their actual sufferers,” he writes. Remember, and put right what is currently wrong, but an apology would be hollow.

I think I could take this a stage further. We can think about other issues beyond slavery, too. There are the problems of truth and reconciliation being faced in countries like South Africa, and which are still to be faced in Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia. How much good does an apology do, there?

The fact that historical wrongs have been committed cannot be changed: what can be changed is whether or not they are repeated. The crucial task to ensure that they are not. In part, this means remembering what has happened, and it may also mean apologies, too, but there is more, besides. There are further actions needed,

What of the demand for compensation, because slavery has left some countries poorer than others. It is certainly true that the countries that profited from slavery are generally richer now than those that suffered from it at the time, but is that down to the legacy of slavery?

If the world is divided into rich, powerful countries and poor, weak ones, the latter are poor because they are weak and not weak because they are poor. What they need most urgently is not wealth but strength. (It is probably not possible to transfuse wealth to any meaningful extent, in any case.)

If the slave trade was a graphic illustration of one country’s ability to impose its will on others, then the correct way to respond now is to control the way in which countries can impose themselves on each other. A framework of law to which each country is subject will stop them doing that: equal access to the law-making for states and citizens will ensure that the law is respected.

A simple apology for slavery might be futile: effective measures to address the problems most certainly would not be.