It has been alarming to watch the leadership of the eurozone limp through the debt crisis affecting some of the member states, apparently as though they have no idea of the scale of what they are facing. The piling-up of debt by countries far in excess of what they can repay is a worry, but a containable worry. Worse is the fear that the crisis spreads to countries with perfectly manageable debt levels, dragged down by a lack of liquidity.

At the height of the first banking crisis in September 2008, the threat of insolvency did for some banks, while the threat of illiquidity did for others. The same threats are present now.

Greece has debts of more than 140 per cent of GDP, a ratio that is likely to grow if austerity drives down GDP faster than it pays back debts. Greece has a solvency problem. As the chart of public debt below shows (data from Eurostat), the same may well be true of Ireland and Portugal.

|

Public debt as % of GDP

|

Public debt (€ billions)

|

Total debt (€billions)

|

|

| Greece |

142

|

329

|

|

| Ireland |

96

|

148

|

|

| Portugal |

93

|

160

|

|

| total (above) |

637

|

||

| Spain |

60

|

638

|

|

| Italy |

119

|

1843

|

|

| overall total |

3118

|

In May 2010, the assembled EU finance ministers established the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) with a fund of €750 billion, which would be more than enough to bail out those three countries. They were adamant that there was no solvency threat to Spain or Italy, and that therefore no funding provision needed to be made for those two.

However, the markets do not necessarily agree with assertions by government ministers. Spain has had a housing bubble, and Italy’s public debt is 119 per cent of GDP. Maybe those countries might find themselves in trouble, too.

And it is in the nature of the financial markets that if they go looking for trouble, they tend to find it. The very act of doubting the future solvency of Spain or Italy starts to drive up borrowing costs (lending to them is riskier) and driving down liquidity (fewer people want to lend), thus impairing the future solvency of the countries that attracted those doubts in the first place. And in this case, the EFSF would be far too small.

There are two ways to deal with threats like this. One is to run away from them. Avoid anything that anyone in the financial markets might worry about. Caution and restraint are the highest values of economic policy. Allow the bond markets to determine policy.

The other is to reclaim the right of governments to make economic policies, recognising that in an interdependent world, those economic policies have got to be made collectively. The markets may be more powerful than any single country on its own, but they are not necessarily more powerful than all the countries acting together.

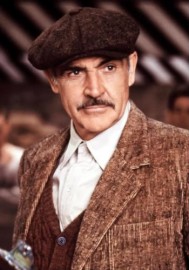

For a start, that means assembling a fund large enough to ensure the liquidity of any member state that might be questioned. Knowing that every member state can be supported means that speculators are not going to waste money picking on them and trying to undermine them. (I am not criticising speculators, merely noting that this is what they do.) Governments need to assemble enough financial power to deter attacks. As Jim Malone, played by Sean Connery, describes the campaign against Al Capone in “The Untouchables”:

They pull a knife, you pull a gun. He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way!

With a fund of perhaps €4 trillion, maybe the leadership of the eurozone at last is learning the lesson.