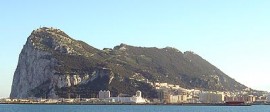

Royal Navy warship HMS Westminster docks in Gibraltar so that the British government can show it is not going to be intimidated by Spanish protests at the border. Spain, which lays claim to the sovereignty of Gibraltar, objects to the creation by the Gibraltarian government of a new artificial undersea reef that will, it claims, affect the fishing prospects for boats in nearby Spanish ports, and is retaliating by making it harder for Gibraltarians to cross the border.

That border dates from 1713, when possession of Gibraltar itself passed from Spain to Britain at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession. Territorial concessions wrung out by war hurt, but the 300 years that have passed since then must surely have eased the pain a little.

The rule of law is a persistent theme on this website, but the law in this case reads rather strangely. The Treaty of Utrecht that secured British ownership of Gibraltar did not do so without conditions. If the Spanish had to give up the isolated fortress, they did not want to open the gates to smuggling, so it was specified that:

the above-named propriety be yielded to Great Britain without any territorial jurisdiction and without any open communication by land with the country round about.

Membership of the EU clearly supersedes any restrictions on communication by land.

Furthermore, Spain in the 18th century still maintained the ban on Jews that it had introduced in 1492 (it was not formally abolished until 1968), and this was written in to the treaty, too:

And Her Britannic Majesty, at the request of the Catholic King, does consent and agree, that no leave shall be given under any pretence whatsoever, either to Jews or Moors, to reside or have their dwellings in the said town of Gibraltar;

Again, the human rights and non-discrimination provisions of the EU treaties would have something to say about this. (And for many years, the chief minister of Gibraltar, Sir Joshua Hassan, was himself a living breach of that clause in the Treaty of Utrecht.)

It is odd, is it not, that the settlement of an international dispute in our modern democratic times should look to a treaty between one autocratic government and another which was only just starting to explore the consequences of democracy. The Glorious Revolution was only 25 years old. Federalism is interested not just in the existence of law but also how that law is made.

It makes no sense now to discuss how a country should be governed without reference to the views of the people who live there. In the case of Gibraltar, those views are pretty clear: the Gibraltarians do not want to be Spanish. Memory of the blockade from 1969 to 1982, lifted by Spain only with the prospect of EU membership in sight, probably has a lot to do with it.

Just because Spain might have a historical claim does not mean that it has a political claim. Democracy and the rule of law must go hand in hand in our modern world.