Parliament has been recalled tomorrow for a debate on the crisis in Syria. The use of poison gas in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta appears to have crossed a line, and western governments are preparing to respond with military force.

There are two related questions to be asked: what is the purpose of any military response; and what would such a response be legal? Let’s take the second question first.

The use of chemical weapons is both peculiarly repugnant and also proscribed by international treaty. Both the 1925 Geneva Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare and the subsequent 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention prohibit their use in warfare: Syria is a signatory of the first but not of the second.

However, given that there are 189 signatories of the Chemical Weapons Convention and only 7 states that have not ratified it, there are legal authorities who claim that this level of support has transformed compliance into a customary norm and thus binding on non-signatory states, too. Geoffrey Robertson QC outlines this argument here (£). (Legal scholars are not all of the same opinion, mind you.)

If Syria is in breach of international law regarding the use of chemical weapons, then military action specifically devoted to punishing and preventing their use might be permissible within international law. Note that this does not require approval by the UN Security Council, although one can imagine what the UNSC members who have so far been blocking action against Syria might think of this.

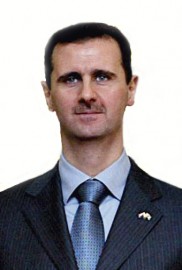

A broader plan to remove President Assad from power – in the name of humanitarian intervention, perhaps, or Responsibility to Protect – would go beyond the terms of the law relating to chemical weapons, and broader UN authorisation would surely be necessary. That broader authorisation would also surely not be forthcoming, as China and Russia would both cast vetoes on the Security Council. It is a strange sort of law that depends on the agreement of autocracies that do not respect the rule of law themselves, but that is the UN in 2013. The Security Council is sometimes an executive, sometimes a legislative body, but here it is being cast in a judicial role: the UN lacks a proper separation of powers.

If all that is likely to be possible, legally, is a limited range of actions to punish and prevent the use of chemical weapons, then the first of my two questions arises: what’s the point?

Preventing the further use of chemical weapons would have some benefits for the people, and especially the non-combatants, of Syria, but President Assad (and his opponents) have proved themselves perfectly adept at killing people by more conventional means. A limited strike against chemical weapons facilities would likely have limited impact on the conflict, but would certainly drag Britain, America and others into the fighting. Is that a good outcome?

It has further been suggested that, whatever the detailed rights and wrong of the issue, American credibility is now on the line. President Obama has drawn a line in the sand and his Syrian opposite number has now crossed it. If there is no reaction now, other countries such as Iran will draw some very ominous conclusions. So even if this is not the best fight to have, it has become a necessary fight.

But going to war in order to confirm a badly-made promise is possibly one of the worst reasons for going to war of all. (I suspect that the intervention in Libya started in a similar way: the proposal to create a no fly zone over Benghazi, on the model of Iraq in 2003, overlooked the fact that Libyan air defences would need to be destroyed first, and turned into an aggressive act and ultimately regime change.) If we had really wanted to get involved in the Syrian conflict, there were plenty of non-military ways to support the democratic opposition that should have been exhausted first, but were not.

Carne Ross wrote here, and Owen Barder wrote here, regarding smart sanctions and support that could and should have been offered. A law that meant that debts incurred by the Syrian government could not be enforced in the courts would have rapidly seen credit to the Assad regime shut off, for example: at last, a socially-useful application for our financial services industry! (One arms shipment was aborted when its marine insurance cover was cancelled.)

We wait to see what kind of plan for which David Cameron seeks authorisation from the House of Commons. Many MPs, remembering the experience of the Iraq war, are sure to demand a much clearer of what is intended and what might be achieved than they ever got from Tony Blair in 2003. Having wasted the last two years failing to support properly the people in Syria with values closest to ours, whatever option is presented in the next few days is sure to be a bad one; the only thing to say for it is that the others may be worse.

¤ ¤ ¤

It is worth reading this commentary on the legal position by Ian Hurd of NorthwesternUniversity, published by Al-Jazeera. He is fairly downbeat that international law is of much help here. He writes:

But the problem is that, legally, the Gas Protocol regulates only wars between states, not civil wars. It does not govern how a government behaves inside its own territory.

If it is true that international law takes the largest and most powerful influences in society, governments, and exempts them from accountability and law – if they really can do what they like in their own territory, then that is a system to which this website is implacably and utterly opposed. The more powerful the organisation, the greater should be the controls to which it is subject.

Gandhi once said, when asked what he thought of western civilisation, that it would be a good idea. I feel the same about international law.

Here is a serious argument that R2P permits military action even if UN Security Council authorisation is withheld: http://www.headoflegal.com/2013/08/28/syria-the-uk-can-legally-use-force/