By John Williams

A review of:

The president of good and evil: taking George W Bush seriously” by Peter Singer (Granta Books, 2004)

“Plan of attack” by Bob Woodward (Simon and Schuster, 2004)

Combined, these two books under review bring into focus the implicit cultural gulf within Atlanticism and the degree to which the Blair Government is divorced from that cultural process as exemplified by the Anglo-American intervention in Iraq.

The aim of Peter Singer’s book, as stated in his Introduction, is to clarify the basis of President George Bush’s moralism, questioning its validity in the process. Thus, perceiving Bush as a symptom of American society, Singer reflects upon American society from as a morally detached perspective as possible.

Singer’s moral detachment becomes questionable almost immediately. Analysing the logical inconsistencies in Bush’s positions on such issues as birth control and the death penalty, he inevitably exposes his own progressive moralism. The problem is that his moral judgements are insufficiently substantiated within a broader frame of political reference.

Although Singer accepts Bush’s sincere Christian beliefs and acknowledges American society is more religious than most, he nonetheless questions the political emphasis that Bush places on religious faith. In doing so, Singer probably underestimates the degree to which Bush personifies the naivety of American society. Thus, according to Singer, Bush’s foreign policy, far from being based on realism as is the conventional wisdom, is based on crude moralism. This begs the question: how does one define American political reality, let alone political reality as such.

Within this context two themes are central to Singer’s analysis. The first is the hegemonic nature of the Bush Administration’s foreign policy, a theme hardly needing emphasis but nonetheless relevant in the extreme. The second is the Administration’s extremely selective use of intelligence in its formulation of foreign policy in relation to its collective, somewhat emotive beliefs. Combined, these two themes are frightening to reflect upon politically.

Singer refuses to accept that Bush is essentially a moral pragmatist in the positive sense. By refusing to accept this Singer ignores the degree to which Bush is a symptom of the American political system, a political system based on the vaguest constitutional definition of freedom which is nonetheless habitually referred to as fundamental to the American way of life. This is not to deny the need to analyse the Bush phenomenon within a broader political context; rather, it is to observe the Bush phenomenon as a symptom of the American political system.

Nevertheless, Singer’s analysis of the Bush Administration’s moral orientation is a useful context within which to view Bob Woodward’s examination of the decision-making processes that led Bush to intervene in Iraq. Here Woodward’s analysis brings out the paranoiac character of the Bush Administration’s decision-making. Focusing on the decision-making processes leading up to the intervention in Iraq, it is an analysis that highlights the inevitability of such an intervention

Such an analysis focuses on the Bush Administration’s overwhelming tendency to concentrate on questions, not of whether, but of what, when, where and how; questions that assume without questioning the assumptions upon which the questions are asked. Political objectives go assumed without either definition or question. Such decision-making logic highlights the increasing criticism of the Bush Administration’s lack of plans for its intervention follow-on. Events occurring whilst reviewing this book merely underline the validity of such criticism.

Woodward’s analysis focuses on the conflict between Dick Cheney, Bush’s hawkish Secretary of Defence, and Collin Powell, his pragmatic Secretary of State, as being the fulcrum of the divisions within the Bush Administration. It is an analysis, validated by The Guardian, that highlights not only the British condition for supporting Bush’s adventure, namely the use of the United Nations as a primary means of implementing the Anglo-American intervention in Iraq, but also the Anglo-American relationship itself.

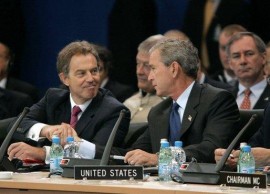

Revealingly, Woodward indicates that Blair’s commitment to the UN stemmed not from ideological principle but from consideration of domestic politics. If accurate, this undermines Blair’s rationale for developing the Anglo-American Special Relationship, namely to modify the excesses of American foreign policy. It reveals Blair’s pragmatism as being rooted, not in well-considered principle, but in hopefully influencing the balance-of-power within the Bush Administration.

It is an analysis that highlights the fact that Blair has opted for the wrong horse in this decision-making balance-of-power struggle. Woodward makes this clear when he relates the conversation between Bush and Powell in which Bush asserts that he opts for war rather than diplomacy as the ultimate means to implement American intervention in Iraq. Such is one of the most damaging contexts within which to place Blair’s political rationale for Anglo-American co-operation. Woodward brings out the moralism underpinning such a political rationale when referring to the fervour of Blair’s commitment to such co-operation.

Woodward’s conclusions, predominantly insightful, are littered with vacuous rhetorical quotes from those most intimately involved in the Iraq intervention. Although initially annoying, these quotes become revealing as to the frenzied atmosphere surrounding the decision-making process.

This article was contributed by John Williams, who may be contacted at [email protected]. The opinions expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of Federal Union. First edition 12/05/04.

More information