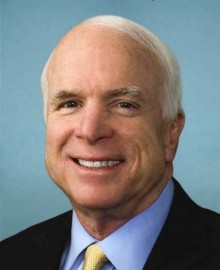

Most of the discussion about the proposal for a league of democracies – floated most notably by Republican presidential candidate John McCain – centres about the notion of democracy. How to choose which countries are eligible and which are not? Can this be done without offending the excluded?

These questions are important, of course, but it is important not to overlook the other half of that proposal, and think about the nature of a league.

If, as is intended, the members of the league include some of the most powerful countries in the world, the role of the league in tempering the way in which they use that power becomes even more important. Some of the criticism of the league proposal is precisely that it will become a means of increasing the power wielded by the powerful: there is no attraction in such an idea for the future of a stable and equitable global order. This criticism has to be addressed.

Fortunately, it can be, precisely because its members are democracies, with political systems based on the idea that the use of political power should be tempered and accountable. This means that the new league should itself be based on the same principles as it demands of its own members, namely that it should be democratic, transparent and accountable, respecting the rule of law.

Both the United States constitution and the treaties that establish the European Union are expressions of these principles. It would be only fitting if, in the 21st century, the US and the EU sought to apply them around the world.